The most important and effective rules for insecticide use over the years have generally employed the words, “do not apply when honey bees are present and/or plants are in bloom.” This is prominently displayed on many chemical controls via the product label, which is now approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for each registered pesticide. So continued attempts to minimize exposure through regulations became increasingly important in determining honey bee safety.

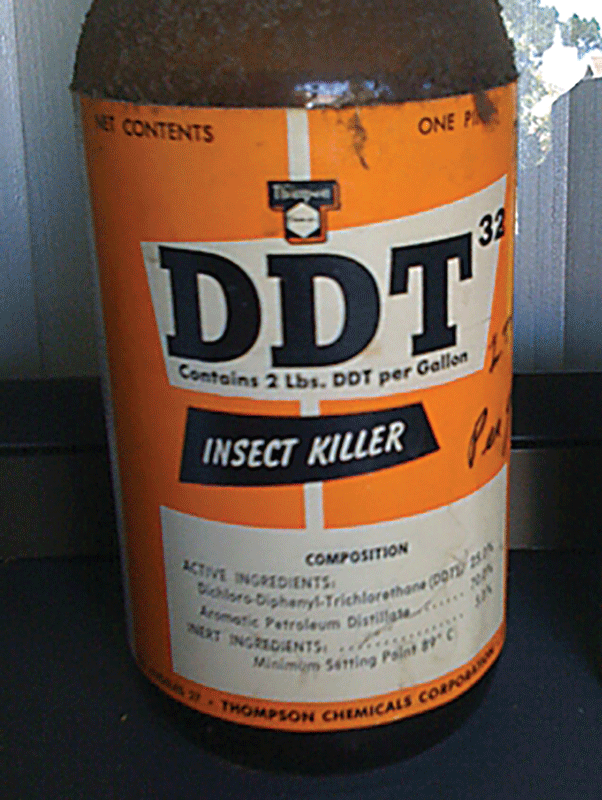

Honey bees, as insects, were generally at greater risk from synthetic organic compounds. The organic food industry further distinguishes between naturally occurring (found in nature) compounds and those that are manufactured (synthetic), often blurring the lines between the chemical definitions of organic versus inorganic. Thus, synthetic organic chemicals have increasingly displaced the dangerous inorganics beginning around 1946, when it was discovered that human lice populations were susceptible. Subsequent research has developed a number of types of alternative synthetic “organic” pesticides, which are more targeted to certain organisms, often insects. It took some investigation by beekeepers and others to finally prove these inorganic chemicals were the culprits in large-scale honey bees kills. They were broad spectrum, inorganic and extremely dangerous materials, often derived from chemical warfare agents. The first pesticides found to be damaging to honey bees were those being applied to agricultural crops, usually as dusts, such as mercury and arsenic. It indicates a relatively more-nuanced idea that pests should be “controlled” only when a certain damaging threshold is reached, and this might mean employing a number of techniques, including possibly physical, biological and chemical means together. Presently many of those intimately involved with these materials refer to themselves as “pest control operators.” “Integrated Pest management” or IPM is another concept becoming more prominent. “Killing” has become a loaded word over the years, so practitioners have increasingly turned to using the word “control” instead.

In an effort to manage the environment, humans have over a long period of time collectively developed chemicals known as “pesticides.” This generic term seeks to bring all the “killing” substances or “cides” under one big umbrella, which includes insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, among a raft of others. With this in mind, the following is offered: Unfortunately, these efforts are all too often not capable of creating a more discerning audience. They incorporate the roles pesticide manufacturers, regulators, researchers, beekeepers and the general public play in keeping specific points of view foremost in the minds of the general public. These tend to emphasize broad-ranging conclusions about these substances that are currently in vogue. Among the materials in this high-risk category are diazinon, Imidan, malathion and Sevin.By Malcolm Sanford A recent spate of articles/comments in Bee Culture has focused on the effects of pesticides on honey bees.

One group of insecticides which is highly toxic to honey bees cannot be applied to blooming crops when bees are present without causing serious injury to colonies. The surprising result has alarmed bee experts because fungicides are targeted at molds and mildews – not insects – but now appear to be a cause of major harm. Are fungicides harmful to insects?Ĭommon fungicides are the strongest factor linked to steep declines in bumblebees across the US, according to the first landscape-scale analysis. Direct exposure to wet sprays or dried residues on leaves or flowers (Figure 2) can kill adult bees. However, although fungicides are generally considered to be relatively safe to bees, scientific evidence has shown that some fungicides can be harmful to bee populations. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested! This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)